July 15, 2007

Op-Ed Contributors

Think Over the Box

By TED BALAKER and SAM STALEY

Los Angeles

AMID the debates — and the looming deadline — over Mayor

Michael Bloomberg’s congestion pricing plans for the city, one

recent traffic measure has caused little uproar: increased

fines ($115) for drivers who block the box. Indeed, many

New Yorkers support the mayor’s plan, which means that not

just regular police officers, but also the city’s more

than 2,800 traffic agents have the authority to hand out

tickets for an infraction known as blocking the box. And why

not? Few things enrage travelers more than the driver who

blocks the intersection, intensifying the already suffocating

traffic congestion.

But the truth is that while this plan may satisfy revenge

fantasies and increase city coffers, it won’t loosen gridlock’s

grip. It may even tighten it.

Blocking the box isn’t a law enforcement issue that

Mayor Bloomberg can address by simply having traffic agents

mete out punishment. It’s a traffic management issue that

represents political neglect of the road network. Drivers

aren’t letting their cars sit in the cross hairs of oncoming

traffic out of spite. They don’t relish the cursing, honking

and fist shaking aimed at them. Like everyone else in the

standstill, they’d prefer to be moving. But there’s just

nowhere to go.

Much of Manhattan’s congestion stems from vehicles passing

through the island on their way to destinations outside or

on the outskirts of the borough. These travelers would love

to bypass most or all of Manhattan, but the roadway network

won’t allow it. Instead it crams motorists together, turning

crosstown travelers into box blockers.

So, here’s the question: If straphangers can choose between

local and express service, why can’t motorists? In cities all

over the world and even in the United States, drivers can choose

to drive up and over intersections on humps called queue

jumpers, or they can duck under intersections through short

tunnels.

Queue jumpers and tunnels could make for a good fit in many

spots throughout New York because they operate within existing

rights of way. They can also be configured for many different

types of roads, from two-lanes on a one-way street (sending

one lane over the intersection) to streets with six or more

lanes.

Just take a look at how effective the Murray Hill Tunnel is

at bypassing traffic. The tunnel, which carries two lanes of

car traffic from East 33rd Street to East 41st Street, is a

great way to avoid the congestion of Park Avenue. Now imagine

more of these tunnels and some well-placed queue jumpers and

soon you’re traveling across town, dodging red lights.

Cities like Paris, Sydney, Melbourne, Tokyo and even

Tampa, Fla., have upgraded beyond queue jumpers to provide

longer under- and aboveground motorways. Granted, much of

the metropolitan region is packed with subway and train

tunnels and other utilities, but elevated facilities need

only airspace, and wide swaths of subterranean space

remain uncluttered.

Consider the western edge of Manhattan, where there are

no serious underground obstructions from the Battery to

the George Washington Bridge. Various east-west streets

are also free of subway tunnels. In the book “Street Smart,”

one contributor, Peter Samuel, makes a sensible suggestion:

construct a truck-only tunnel that would take many

lane-cloggers off surface streets. “It would feed a

north-south truckway spine along the west side of Manhattan,

with short east-west spurs,” he writes.

Gridlock hasn’t grown fiercer because drivers have become

ruder and simply no longer care if they block the box.

Rather, clogged intersections represent a symptom of

congestion’s root cause: political neglect.

For decades, officials have failed to upgrade the road network

to keep up with a swelling population. Mayor Bloomberg has said

that the city will grow by 900,000 people by 2030; if this

neglect continues, it will generate even more gridlock. Over

the next 20 years city forecasters expect automobile traffic

to grow by 10 percent and freight traffic to increase major

transportation recommendations in the city’s long-range plan,

not one would significantly increase the road system’s

capacity.

Mayor Bloomberg’s ironfisted approach to intersection blockers

not only allows an outdated roadway system to grow more

antiquated, it may also erode support for congestion pricing.

Cities like London and Stockholm have found it easier to sell

the public on congestion pricing when road projects are a part

of the deal, and New York should follow suit. After all, most

of those who would pay the $8 congestion toll — if the plan

is approved by Albany in time to meet tomorrow’s federal

deadline for a grant of about $500 million for the

program — aren’t out-of-towners, they’re the mayor’s own

constituents.

As we await news from Albany, many remain suspicious of

congestion pricing, and they won’t take kindly to additional

measures that cast drivers as scapegoats. Promising to devote

some congestion pricing money to building queue jumpers may

win over fence-sitting motorists, not to mention bus riders

who would enjoy bona fide express service.

Ted Balaker, a fellow at the Reason Foundation, and

Sam Staley, the director of the organization’ s urban and

land use policy, are the authors of “The Road More Traveled:

Why the Congestion Crisis Matters More Than You Think, and

What We Can Do About It.”

Copyright 2007 The New York Times Company

http://www.nytimes.com/2007/07/15/opinion/nyregionopinions/15CIbakalar.html?ex=1185595200&en=53fe13b2c65f78f4&ei=5070

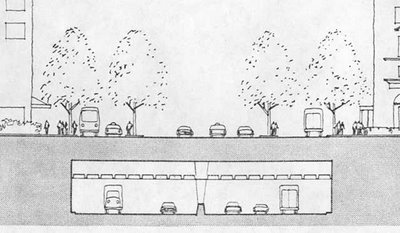

Truck (Interstate Highway design standard) Tunnel

under existing right if way

(un-built Washington, D.C. I-66 K Street Tunnel)

Its' east-west spurs would logically include some variant of the underground proposals for at least a portion of the un-built Midtown Manhattan Expressway; similarly it could include an underground replacement for the un-built Lower Manhattan Expressway via a Canal Road Bypass Tunnel drilled beneath historic So Ho.

Logical additions would include a 4th tube for the Lincoln Tunnel, and at least a pair of new, modern specification 2 lane tubes paralleling the Holland Tunnel.

Regionally, it should be accompanied by the Gowanus Tunnel Project (with a tunneled extension north-easterly to bypass the Promenade), along with a Cross Harbor-Brooklyn Highway-Railway Tunnel from I-78 in New Jersey to the Conduit Avenue corridor (with Interboro spur), providing a valuable evacuation route from Long Island.

No comments:

Post a Comment