http://www.permatopia.com/icc/icc-deis-2005-comments.pdf

http://www.permatopia.com/icc/icc-deis-2005-comments.pdf(excerpt- at page 15)

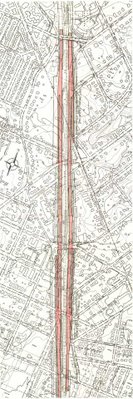

If the ICC is truly intended to boast "Homeland Security", then additional analysis (in a SDEIS) is needed to determine the feasibility and need for reviving the 1950s era proposal for extending Interstate 70 South (the original name or I-270) inside the Beltway to downtown DC. This proposed road would run through Northwest Washington, near the new headquarters of the Department of Homeland Security (at the former Naval Security Station, next to American University).That was the radial highway that would have passed through Washington's wealthiest, whitest area, taking fewer homes than either the corresponding NCF or NE Freeway as shown in the 1959 Mass Transportation Plan, about 74 from the Maryland line at Friendship Heights to the north head of Glover Archibold Park to continue there south as a parkway, with the 1959 plan featuring a split to an I-70 continuation that would have displaced a few dwellings at the northern edge of the Cleveland Park neighborhood before crossing Rock Cree Park to a continuation through the Mt Pleasant neighborhood that would have displaced far more dwellings to an interchange with the I-66 North Leg of the Inner Loop.

1959 Cleveland Park

(dashed lines indicate tunnel segments)

(dashed lines indicate tunnel segments)

1959 Mt. Pleasant

(no tunnel segments in less affluent areas)

(no tunnel segments in less affluent areas)

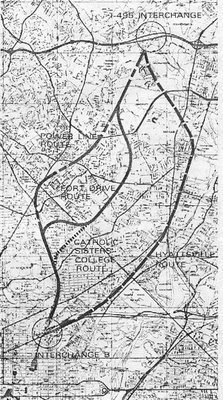

The cancellation of the NW Freeway led to the 1962 JFK Administration proposal of replacing the 1959 plan for three separate northern radial freeways with a 2 into 1 "Y" Route upon the B&O Metro Branch RR-industrial corridor that runs next to the campus of Catholic University of America. This was to occur with essentially the rail transit network that was built for WMATA.

That plan would be effectively undermined politically via the subsequent 1964 North Central Freeway reports' failure to follow the JFK plan with up to 37 studied routes largely nowhere near this rr and with a recommendation running along the rr in some areas only to deviate significantly directly through old neighborhoods with far far higher local impacts -- 471 free standing dwellings for the 1 mile segment through Takoma Park, Maryland upon a route not only far more destructive but longer and less direct then JFK's B&O "Y" route.

1964

Veers about 1/2 mile away from the B&O railroad on new swath through old neighborhoods in Takoma Park, Maryland, taking 471 houses for the 1.1 mile segment, before rejoining the railroad immediately north of New Hampshire Avenue.

Veers about 1/2 mile away from the B&O railroad on new swath through old neighborhoods in Takoma Park, Maryland, taking 471 houses for the 1.1 mile segment, before rejoining the railroad immediately north of New Hampshire Avenue.

This route was longer and less direct.

Route #11 at New Hampshire Avenue, veering away from the B&O railroad into Takoma Park

Route #11 at New Hampshire Avenue, veering away from the B&O railroad into Takoma Park

Veers about 1/2 mile away from the B&O railroad on new swath through old neighborhoods in Takoma Park, Maryland, taking 471 houses for the 1.1 mile segment, before rejoining the railroad immediately north of New Hampshire Avenue.

Veers about 1/2 mile away from the B&O railroad on new swath through old neighborhoods in Takoma Park, Maryland, taking 471 houses for the 1.1 mile segment, before rejoining the railroad immediately north of New Hampshire Avenue.This route was longer and less direct.

Route #11 at New Hampshire Avenue, veering away from the B&O railroad into Takoma Park

Route #11 at New Hampshire Avenue, veering away from the B&O railroad into Takoma Park

1964

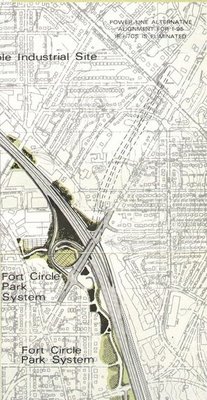

1966

It was not until 1966 that a "supplementary" North Central Freeway study with the JFK B&O route appeared; it eliminated the separate swath in Takoma Park by "hugging" the railroad's flanks at the edge of Takoma Park, with various sort tunnels to swing the highway to one side or the other railroad, such as alongside Montgomery Community College, with a proposal to effectively do the same alongside Catholic University and Brookland via "air rights" development.The 1971 plan extends the highway cover southward to Rhode Island Avenue, yet inexplicitly deletes the northern segment alongside the main campus of Catholic University of America, continuing its traditional isolation from the east .

All of this was undermined by various politician's suggestions as late as 1968 in favor of the earlier route from 1964 as "less expensive".

So would a change in the route in the vicinity of Fort Totten to use more parkland, creating a new objection in the 1966-71 plan absent from the 1964 plan.

So conceivably did the 1971 plan's to bury the highway segment through Takoma, D.C., but with a catch: whereas the 1966 plan flanked the railroad -- that is a 3/RR/RR/3 configuration -- the 1971 plan placed both directions of the highway along the railroad's eastern side, thus placing it in direct conflict with the landmark Cady-Lee mansion on the corner of Eastern Avenue and Piney Branch, necessitating its removal, whereas the 1966 plan avoided this.

1966 I-70S

1966 I-70SCut and cover tunnels

Silver Spring, Maryland

alongside Blair Park/Montgomery Community College

No plan was drawn up via the authorities to tunnelize this segment of highway with highway carriageways flanking the railroad to preserve the Cady Lee mansion as well as the houses to the north facing Takoma Avenue. The Cady Lee mansion, built cir 1884, is the northernmost house within D.C. along the railroad's eastern side.

Why add objections lacking in earlier plans?

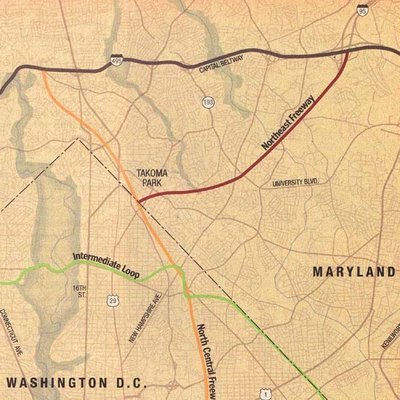

Doing so would only continue to undermine this highway's political support, doing so pretty much by the time of the final re-routing with the change of the I-95 Northeast Freeway's route from Northwest Branch Park/Fort Drive, to the PEPCO power line/New Hampshire Avenue route.

D.C. I-95 Northeast Freeway routes

1960-1973

1960 report has I-95 in Maryland via Northwest Branch and entering D.C. passing alongside Catholic Sisters College; that route is openly opposed by the Roman Catholic Church and the adjoining residential areas, leading to its re-routing within D.C. via the Fort Drive right of ay between Galatin and Galloway Streets NE. The subsequent PEPCO Power Line right of route was developed in the 1971 report, replacing the Northwest Branch-Fort Drive route in order to preserve parkland and re-utilize n existing 250 foot clear cut power line right of way extending from outside the I-495 Capital Beltway to some 1,600 or so feet from the Maryland D.C. line alongside New Hampshire Avenue, to then travel about another 1,600 feet to join the B&O railroad corridor.1960-1973

In my studies of numerous historical information sources regarding this highway planning, I have yet to encounter anything on the Order of the Eastern Star's opinions- for instance did they ever request making the depressed segment through their property as a tunnel to preserve the home's sanctity?

Likewise with that of Catholic University of America- did they for instance object to the proposed highway lid's shortening in the 1971 plan versus the 1966 plan which extended further north alongside the CUA main campus to Taylor Street?

The Washington Post would completely misrepresent this route

in its November, 2000 article "Lost Highways" by Bob and Jane Levey, with this map turning the I-95 Northeast route away from its New Hampshire Avenue routing through the field of the Order of the Eastern Star Masonic home, and upon a highly destructive and fictitious route that appears in no planning documents

in its November, 2000 article "Lost Highways" by Bob and Jane Levey, with this map turning the I-95 Northeast route away from its New Hampshire Avenue routing through the field of the Order of the Eastern Star Masonic home, and upon a highly destructive and fictitious route that appears in no planning documents

No northern D.C. radial highway appears in official planning documents after 1973.

A Future Washington, D.C. Big Dig

North Central Freeway- A Trip Within The Beltway

Northeast Freeway- A Trip Within The Beltway

Northwest Freeway- A Trip Within The Beltway

Evacuation Routes- A Trip Within The Beltway

The Washington Post Lies About D.C. I-95

1 comment:

Tunnel boring machines allow inexpensive creation of tunnels. These were not available in the 1960s. Extending I-270 through the wealthy neighborhoods of Northwest Washington would be possible without tearing out any structures. Ingress and egress from monumental Washington would be possible for Homeland Security purposes. The tunnel would be expressly limited access. No D.C. ramps except in the center of Washington City.

Post a Comment