and keep any such freeway far away from, let alone through the field of the Masonic Eastern Star Home on New Hampshire Avenue

As with anything, just connect the dots with the most influential property owners along a given route...excerpted from:

http://cos-mobile.blogspot.com/2008/07/homeland-security-goal-would-be-better.html

The cancellation of the NW Freeway led to the 1962 JFK Administration proposal of replacing the 1959 plan for three separate northern radial freeways with a 2 into 1 "Y" Route upon the B&O Metro Branch RR-industrial corridor that runs next to the campus of Catholic University of America. This was to occur with essentially the rail transit network that was built for WMATA.

That plan would be effectively undermined politically via the subsequent 1964 North Central Freeway reports' failure to follow the JFK plan with up to 37 studied routes largely nowhere near this rr and with a recommendation running along the rr in some areas only to deviate significantly directly through old neighborhoods with far far higher local impacts -- 471 free standing dwellings for the 1 mile segment through Takoma Park, Maryland upon a route not only far more destructive but longer and less direct then JFK's B&O "Y" route.

1964

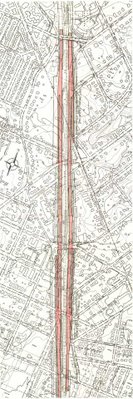

Veers about 1/2 mile away from the B&O railroad on new swath through old neighborhoods in Takoma Park, Maryland, taking 471 houses for the 1.1 mile segment, before rejoining the railroad immediately north of New Hampshire Avenue.

Veers about 1/2 mile away from the B&O railroad on new swath through old neighborhoods in Takoma Park, Maryland, taking 471 houses for the 1.1 mile segment, before rejoining the railroad immediately north of New Hampshire Avenue.

This route was longer and less direct.

Route #11 at New Hampshire Avenue, veering away from the B&O railroad into Takoma Park

Route #11 at New Hampshire Avenue, veering away from the B&O railroad into Takoma Park

Veers about 1/2 mile away from the B&O railroad on new swath through old neighborhoods in Takoma Park, Maryland, taking 471 houses for the 1.1 mile segment, before rejoining the railroad immediately north of New Hampshire Avenue.

Veers about 1/2 mile away from the B&O railroad on new swath through old neighborhoods in Takoma Park, Maryland, taking 471 houses for the 1.1 mile segment, before rejoining the railroad immediately north of New Hampshire Avenue.This route was longer and less direct.

Route #11 at New Hampshire Avenue, veering away from the B&O railroad into Takoma Park

Route #11 at New Hampshire Avenue, veering away from the B&O railroad into Takoma Park

1964

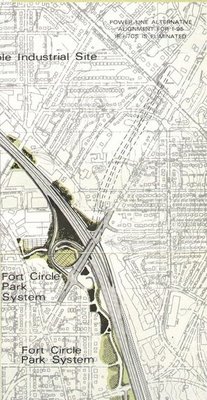

1966

It was not until 1966 that a "supplementary" North Central Freeway study with the JFK B&O route appeared; it eliminated the separate swath in Takoma Park by "hugging" the railroad's flanks at the edge of Takoma Park, with various sort tunnels to swing the highway to one side or the other railroad, such as alongside Montgomery Community College, with a proposal to effectively do the same alongside Catholic University and Brookland via "air rights" development.The 1971 plan extends the highway cover southward to Rhode Island Avenue, yet inexplicitly deletes the northern segment alongside the main campus of Catholic University of America, continuing its traditional isolation from the east .

All of this was undermined by various politician's suggestions as late as 1968 in favor of the earlier route from 1964 as "less expensive".

So would a change in the route in the vicinity of Fort Totten to use more parkland, creating a new objection in the 1966-71 plan absent from the 1964 plan.

So conceivably did the 1971 plan's to bury the highway segment through Takoma, D.C., but with a catch: whereas the 1966 plan flanked the railroad -- that is a 3/RR/RR/3 configuration -- the 1971 plan placed both directions of the highway along the railroad's eastern side, thus placing it in direct conflict with the landmark Cady-Lee mansion on the corner of Eastern Avenue and Piney Branch, necessitating its removal, whereas the 1966 plan avoided this.

1966 I-70S

1966 I-70SCut and cover tunnels

Silver Spring, Maryland

alongside Blair Park/Montgomery Community College

No plan was drawn up via the authorities to tunnelize this segment of highway with highway carriageways flanking the railroad to preserve the Cady Lee mansion as well as the houses to the north facing Takoma Avenue. The Cady Lee mansion, built cir 1884, is the northernmost house within D.C. along the railroad's eastern side.

Why add objections lacking in earlier plans?

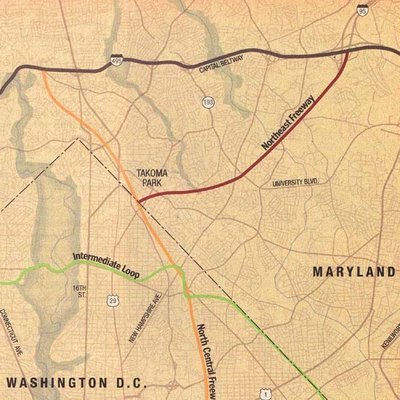

Doing so would only continue to undermine this highway's political support, doing so pretty much by the time of the final re-routing with the change of the I-95 Northeast Freeway's route from Northwest Branch Park/Fort Drive, to the PEPCO power line/New Hampshire Avenue route.

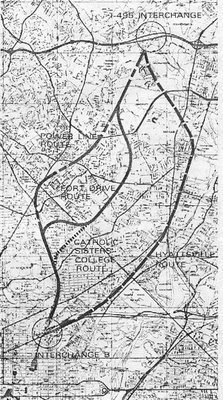

D.C. I-95 Northeast Freeway routes

1960-1973

1960 report has I-95 in Maryland via Northwest Branch and entering D.C. passing alongside Catholic Sisters College, which was openly opposed by the Roman Catholic Church and the adjoining residential areas, leading to its abandonment.1960-1973

The November 1962 White House report retains the Maryland Northwest Branch routing, while, for D.C. adopting the Fort Drive right of way between Galatin and Galloway Streets NE- which is the routing adopted by the subsequent 1964, 1966 and 1971 study-reports.

The 1971 study-report presents that option of the subsequent PEPCO Power Line right of route, in order to preserve parkland by instead re-utilizing the existing 250 foot clear cut power line right of way that extends from outside the I-495 Capital Beltway to some 1,600 or so feet from the Maryland D.C. line alongside New Hampshire Avenue, to then travel about another 1,600 feet to join the B&O railroad corridor.

Below is the most significent property along the connecting segment of B&O-PEPCO I-95.

-------

Masonic Eastern Star Home

Masonic Eastern Star Homeon New Hampshire Avenue

between railroad and the Washington, D.C.-Maryland line

http://www.mei-futures-dc.org/campusThis Masonic Order appears to possess an affinity for this side of Washington, D.C.'s New Hampshire Avenue, expressed with the early 1900s creation of the Order's Home on 6000 New Hampshire Avenue NE near the border with Maryland, quickly followed by the 1906 start of construction of what became its downtown headquarters new DuPont Circle, at 1618 New Hampshire Avenue NW:

the beautiful, historic grounds of the Masonic and Eastern Star Retirement Home at 6000 New Hampshire Avenue, NE, Washington, DC 20011.The home was built in 1905 and has retained much of the original architecture throughout recent renovations.

-------The Perry Belmont Mansion is one of Washington’s finest examples of Beaux Arts architecture. Designed by French architect Eugene Sanson [started in 1906] and completed in 1909, the house remains today much as it was when originally constructed and still contains many of the Belmonts furniture and objects d’art. Mr. Belmont was the grandson of Commodore Perry who negotiated the 1854 Treaty of Amity, which opened the ports of Japan for commerce. During the sixteen years that Jessie and Perry Belmont, who had served as US Ambassador to Spain, occupied the house, dignitaries from around the world were entertained there. The landmarked house was purchased in 1935 by the Order of the Eastern Star for use as its international headquarters. It serves also as the private residence of the Right Worthy Grand Secretary. The Order’s careful stewardship provides Washington with a remarkable example of its built heritage.

Formerly the Perry Belmont Mansion, it was started in 1906 and completed in 1909, at the then-extravagant cost $1.5 million. Perry and Jessie Belmont built the mansion for the specific purpose of entertaining not only notables of Washington, but also dignitaries from all over the world. The building was only used during the Washington party season (about two months each year) and special events. It was designed by Eugene Sanson, a famous French architect who had designed many grand homes and chateaus in Europe. He was renowned for his use of light and space, and for his beautiful staircases. Long before the acquisition of the building by the General Grand Chapter in 1935, it was a site of elegance, gracious and grand hospitality, of distinguished diplomats, world-renowned guests and romance.

The Belmonts entertained lavishly and had a staff of approximately 34 servants. They used the house from 1909 to 1925. It was then closed and put on the market for sale with the stipulation that it could not be altered for 20 years after purchase. The mansion stood empty and unused until 1935, when the General Grand Chapter purchased it. Mr. Belmont, being a Mason and happy to be selling it to someone who would take care of it, sold it to The General Grand Chapter for $100,000. As part of our agreement with Mr. Belmont, The General Grand Chapter law states the Right Worthy Grand Secretary must live in the Temple. So the building is still a working private residence as well as our headquarters. Many furnishings, including several Tiffany vases, 37 oil paintings, Louis the 14th and 15th furniture, china and oriental rugs were included with the purchase of the Temple and are still on display for our members and their guests to enjoy on tours. Chandeliers throughout are gold gilt and hung with hand-carved rock crystal drops – some with amethyst as well. There are eleven fireplaces, most with hand-carved marble mantles. All the marble in the house was brought from Italy, all the wood from Germany and all the metal fixtures from France.

Likewise with that of Catholic University of America- did they for instance object to the proposed highway lid's shortening in the 1971 plan versus the 1966 plan which extended further north alongside the CUA main campus to Taylor Street?

The Washington Post would completely misrepresent this route

in its November, 2000 article "Lost Highways" by Bob and Jane Levey, with this map turning the I-95 Northeast route away from the field of the Order of the Eastern Star Masonic home property alongside New Hampshire Avenue between the RR and the D.C./Maryland line, and instead upon a highly destructive and fictitious route that appears in no planning documents

in its November, 2000 article "Lost Highways" by Bob and Jane Levey, with this map turning the I-95 Northeast route away from the field of the Order of the Eastern Star Masonic home property alongside New Hampshire Avenue between the RR and the D.C./Maryland line, and instead upon a highly destructive and fictitious route that appears in no planning documents

http://wwwtripwithinthebeltway.blogspot.com/2007/02/sampling-of-attitudes-towards-dc-i-95.html

http://cos-mobile.blogspot.com/2009/05/romish-masonic-religious-drive-against.html

http://wwwtripwithinthebeltway.blogspot.com/2008/12/who-really-stopped-washington-dcs.html

http://wwwtripwithinthebeltway.blogspot.com/2009/05/telling-deletion.html

http://cos-mobile.blogspot.com/2009/05/romish-masonic-religious-drive-against.html

http://wwwtripwithinthebeltway.blogspot.com/2008/12/who-really-stopped-washington-dcs.html

http://wwwtripwithinthebeltway.blogspot.com/2009/05/telling-deletion.html

No comments:

Post a Comment